ARLINGTON, Texas—“I honestly don’t think getting around Arlington is as bad as [everyone] says, but it’s still a shame, because if it were just a little easier to cross from my apartment to Abrams [Street], it would go a long way,” University of Texas at Arlington mechanical engineering student Juan Ramirez said.

Ramirez said he used to traverse the city as a freshman with his friends, back when he had more time, but lately the student decided it was no longer worth the hassle. He said that “crazy Arlington drivers” and “misplaced crosswalks” have become a common annoyance when getting around.

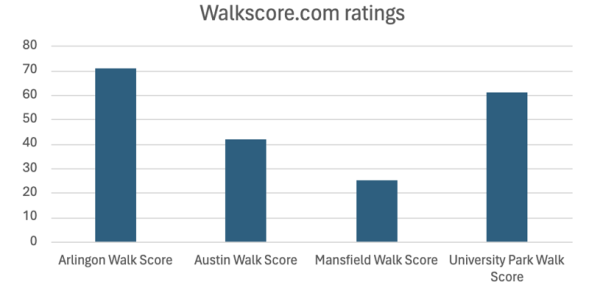

Arlington, Texas, is known nationally as the largest city in the country without a traditional public transport system — but whether that fact has anything to do with the city’s overall walkability is debatable.

Emblematic of the Sunbelt growth surge post-World War II, Arlington has long been synonymous with automobile dominance. Its sprawling urban landscape, with roots stretching back to the 1960s and ‘70s, has been shaped by a development ethos centered on vehicular convenience. But as the tides of urban planning evolve, questions arise about Arlington’s walkability and its readiness for a more pedestrian-friendly future.

“In Arlington’s case, really since the 1960s, early 1970s, the urban form was very much dominated by the automobile,” Alan Klein, UTA director of urban studies, said.

The initial blueprint of the city, especially in areas west of the campus, echoes this sentiment. While pedestrian amenities like sidewalks and marked crossings existed, the focus predominantly veered toward ensuring safe and efficient vehicular flow.

The result? A cityscape tailored to automotive convenience rather than foot traffic.

Although the infrastructure was built up with vehicles in mind, efforts are underway to recalibrate Arlington’s urban fabric toward greater walkability. Downtown Arlington Inc. has spearheaded initiatives to enhance pedestrian experiences, within a limited geographical scope.

Abram Street’s metamorphosis serves as a beacon of hope for proponents of pedestrian-centric design. What was once solely dedicated to automobiles underwent a transformation, embracing medians, sidewalks and enhanced pedestrian amenities. Such endeavors, while commendable, underscore the persistent challenges in retrofitting urban spaces designed primarily for cars.

“The critical issue in terms of being a more walkable and bikeable community is better connections from Arlington to the downtown area,” Klein said.

In an audit conducted by Walkable Arlington, a grassroots organization promoting walkability, a team found that even a 12-minute bike ride from UTA poses several problems.

According to the audit, the greatest barrier the team faced was “crossing South Fielder Street from West Second to Norwood Lane.” No bike lanes or sidewalks are present for pedestrians to cross Fielder.

The audit revealed glaring gaps in pedestrian infrastructure, highlighting the pressing need for tangible improvements.

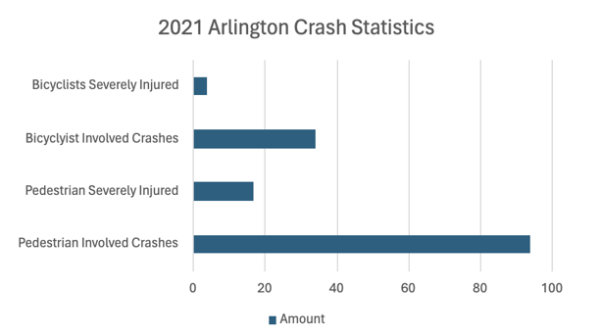

Similar issues were noted from other teams—lack of pedestrian infrastructure means people are led to take strenuous detours or even worse, to jaywalk.

Bike lanes face an uphill battle for acceptance in Arlington’s urban milieu. Political opposition, particularly in areas west of the campus, impedes progress toward comprehensive bike facilities. Buffered bike lanes, essential for ensuring cyclists’ safety, remain a distant dream as the city grapples with reconciling competing interests and bureaucratic hurdles.

The intricacies of urban planning come to the fore in Arlington’s narrative. Major roadways like Cooper Street and Division fall under the purview of the Texas Department of Transportation, necessitating a complex interplay of municipal and state-level approvals for transformative pedestrian infrastructure projects.

Moreover, the reluctance to embrace pedestrian-friendly design stems from apprehensions regarding economic viability. The notion that reduced automobile access translates to dwindling customer footfall persists despite evidence suggesting otherwise. Educating stakeholders about the economic benefits of pedestrian infrastructure becomes imperative in fostering a paradigm shift toward walkability.

There are two distinct processes governing infrastructure improvements within the city. Sabino Martin, Arlington project engineer, shed light on this dual framework, delineating between projects falling under the purview of the Texas Department of Transportation and those directly managed by the City of Arlington.

Martin said Arlington can’t just make changes to roads like Cooper, which are the responsibility of the state.

Citizens play a pivotal role in initiating infrastructure requests, with avenues for direct engagement outlined on the city’s website. From sidewalk repairs to crosswalk installations, residents can submit requests directly to the City of Arlington, setting in motion a review process spearheaded by the sidewalk program manager. But in a question and answer section of the city website outlining how citizens can request sidewalks in their neighborhood, the city notes, “Surprisingly, very few neighborhoods are receptive to the addition of new sidewalks.” The city also notes that “[f]unding for new sidewalks is very limited.”

Funding mechanisms shape the trajectory of all infrastructure projects, with allocations dictated by municipal bond programs. Every four to five years, citizens vote on bond initiatives, earmarking dedicated funds for various infrastructure endeavors, including sidewalk enhancements and safe routes to school. With an annual budget of approximately $1.4 million, the city channels resources toward addressing the evolving needs of its burgeoning population.

Amid projections of continued population growth, long-term planning assumes paramount importance in shaping Arlington’s urban landscape. New developments adhere to the Unified Development Code, mandating the inclusion of sidewalks to foster walkability from the outset. For existing infrastructure, citizen input serves as a guide, informing the prioritization of sidewalk installations and pedestrian amenities.

But the quest for walkability necessitates a delicate balance between competing interests. The symbiotic relationship between pedestrian infrastructure and vehicular access emerges as a focal point in urban planning deliberations. Strategic road reconstructions, like the revitalization of Abram Street, exemplify a concerted effort to prioritize pedestrian needs while mitigating potential disruptions to vehicular traffic.

“In terms of looking at how we provide for pedestrians and cyclists, we always provide that walkability as far as cyclists,” Martin said. “We do have a hike and bike trail plan that we have developed.”

Metrics for assessing the efficacy of infrastructure improvements revolve around pedestrian safety and accessibility. Post-implementation evaluations identify usage patterns and areas warranting additional enhancements. Citizen feedback serves as a crucial barometer, guiding iterative improvements aimed at fostering a safer and more accessible urban environment for all residents.