NAGAOKA, Japan—Municipalities across the globe are wrestling with the impact of a changing climate and how best to build resilience for their communities in the face of severe weather events.

Some communities began engaging in this work only recently. Others, like those in Japan’s Niigata Prefecture, have been at it much longer.

The Ohkouzu Diversion Channel has served for nearly 100 years to protect the people of the Echigo Plain from frequent flooding of the Shinano River, which at 228 miles in length is Japan’s longest waterway. Roughly 178 miles north of the towering skyscrapers and flashing billboards of Tokyo, this human-made marvel has opened the region to productive agriculture and economic development.

A boon to agriculture

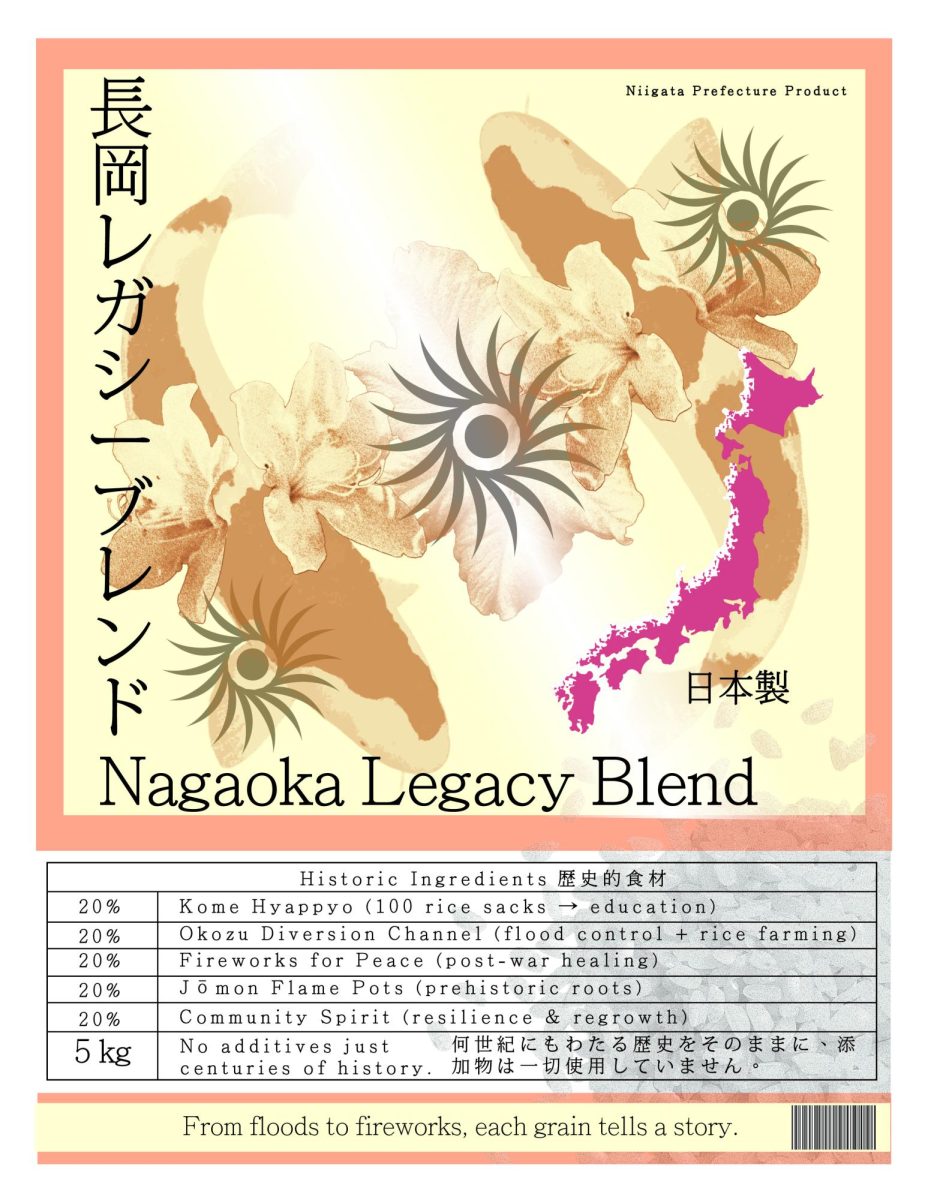

Thanks to the Ohkouzu Diversion Channel, Niigata today is No. 1 in Japan for rice production.

“Niigata prefecture where Nagaoka [is located] is now well-known as ‘komedokoro,’ the place for rice,” Chikako Jinnai of the Nagaoka International Exchange Association said. “But it does not have a long history. After this huge construction of the Ohkouzu Diversion Channel, we are able to produce good rice.”

According to “The Shinano River Ohkouzu Museum Guidebook,” rice in Niigata prior to the channel was disparaged as “Torimatagi-mai,” or “rice that is so bad that even birds will step over it without eating it.” That changed solely because of the Ohkouzu Diversion Channel.

Today, the river-diversion project stands as testimony to the power of engineering to help communities live in harmony with a changing climate. Indeed, Nagaoka’s Sister City of Fort Worth, Texas, is planning to employ a river diversion of its own with its Panther Island flood control project, and Arlington, Texas, has undertaken multi-million dollar flood mitigation work.

Before the creation of the diversion channel, which directs excess water to the Sea of Japan, the Shinano River often flooded during heavy rainfall.

Nature and manpower

Each flood disrupted life in the Echigo Plain. In addition to the damage done to homes and infrastructure, farmland became too wet to work effectively or efficiently. Not only did this hinder the region’s ability to produce food for its residents, it hurt the overall economy while it muddled and endangered lives. To prevent the flooding and protect the residents’ way of life, the Ohkouzu Diversion Channel was born.

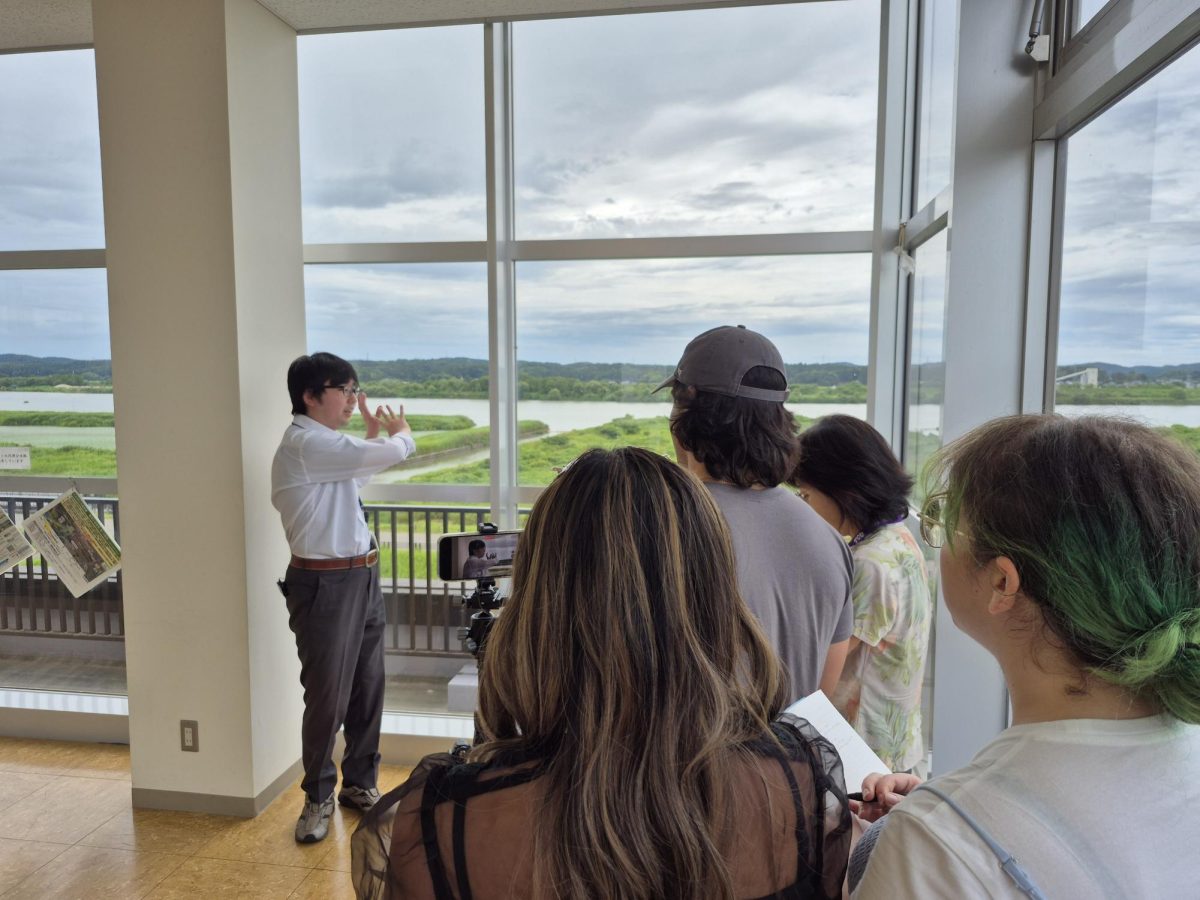

Today, from the fourth floor of the Shinano River Ohkouzu Museum, visitors can take in a nearly 360° view of the river and diversion channel in all their glory. Visitors can view the weirs and watch as the water flows through the river and the channel. Surrounding the waterways, bountiful rice paddies seem to roll in the breeze—an amazing view, and one that subtly highlights the combination of nature and manpower.

The river at the point of diversion is much wider than the channel itself, narrowing down from roughly 2,362 feet down to about 591 feet. That narrowing can make it difficult for the water to flow out to the sea and can be a threat to those living alongside it. To help relieve this issue, construction efforts have begun to widen the channel and aid in the flow.

Ohkouzu Diversion Channel history

While the Ohkouzu Diversion Channel has been operating successfully and keeping the plain safe for nearly 100 years, things haven’t always flowed so smoothly.

The Shinano River has long served as a vital lifeline—and threat—to those who live near it. The river supports transportation, trade, agriculture and is a home for wildlife and vital ecosystems. Originating at Mount Kobushi in the Japanese Alps, the river flows northwest and out to the Sea of Japan in Niigata City. Spring snowmelt, typhoons and Japan’s summer rainy season led to repeated flooding of the Echigo Plain.

For more than 200 years, locals petitioned for a diversion that redirected the flood water into the Sea of Japan. In 1868, when a great flood covered the Echigo Plain, residents increased pressure on their local governments to act. Countless floods had taken people’s lives, harmed their food and water, and spread disease in the area.

A year later, the Meiji government agreed to begin river diversion work, but a lack of funding prevented it from moving quickly. After another devastating flood in 1896, it was clear that a diversion channel was a necessity, and the project needed to be completed this time around.

Construction on the channel restarted in 1906 and continued until 1922. Civil engineering systems were joined with human-made and natural infrastructure to create the roughly 6.2-mile diversion channel. Tools and machines were imported from the West, including countries like Germany, England and France. These machines, useful as they were, were not enough to complete the job.

Muscle power

It took the equivalent of more than 10 million working men and women to complete the project. While men worked to excavate the path by removing earth and rock, women pushed carts full of the debris to transport it from the digging sites. These carts weighed roughly 220 pounds even before being loaded with rocks. Women were paid by how many carts they transported, and legend has it that men would only partially fill carts if they had a fondness for the women pushing them.

All told, the diversion required workers to move 28.8 million cubic meters of earth—the equivalent of 27.4 Empire State Buildings. That much dirt and rock would fill more than 11,520 Olympic-size swimming pools.

Moving earth to create a channel to the Sea of Japan was only a part of the project. The channel’s continued success relies upon weirs that help regulate the flow of water in both the Shinano River and in the Ohkouzu Diversion Channel.

The operation of the weirs is coordinated to ensure that the river’s flow is maintained at 270 cubic meters per second, the amount necessary to meet downstream water demand. Excess water is directed through the diversion channel and out to the Sea of Japan.

The weirs are supplemented by ground sills, concrete structures built across the water channels to slow the speed of the water and to help regulate sediment and prevent erosion.

At the time of its construction, the project cost ¥23.5 million, equivalent to the entire budget for Niigata prefecture at that time. That works out to about $12 million in 1920 dollars, or nearly $194 million today.

But as costly as the diversion channel was financially, its real cost can be measured in human life. About 100 people died excavating and building the channel.

Despite the financial and human costs, the Ohkouzu Diversion Channel has stabilized both the Shinano River’s flow and the lives of area residents.

“Even if it rains enough to cause a major flood, the flood diversion channel prevents the water from flowing into the Echigo Plain, so in that sense, I think people are able to live a safe life now,” said Masanori Kanno, chief of the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism’s Shinano River Management Office planning section. “And as for rice cultivation, it’s now one of Japan’s leading grain producing areas, so I think it’s essential in that sense.”

Although the Ohkouzu Diversion Channel is considered an engineering success story, it hasn’t functioned flawlessly. In 1927, the diversion weir collapsed and took roughly four years to fix. In 1973, an additional weir was added farther along the channel to help prevent and manage erosion of the riverbed. Because the flow of the river cannot be stopped, every repair and modification to the channel must be done as water continues to flow, Kanno said.

If the weirs were to collapse, the water flow could cause damage all the way down to Niigata City, a major port and home to nearly 800,000 people. Severe floods would destroy farms, land, homes and industries.

The challenge of a changing climate

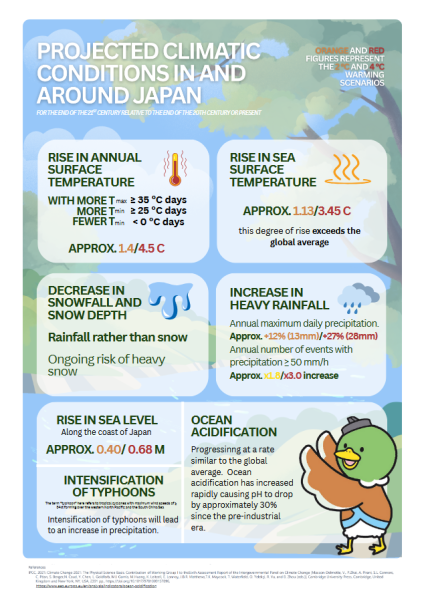

As with many countries in the 21st century, Japan has encountered new problems due to ongoing climate change. As an island nation, Japan is susceptible to rising sea levels. And in Nagaoka, residents are feeling the impact of severe weather events on two fronts: agriculture and weather.

Nagaoka, as a city, prides itself on the rice production possible because of the Ohkouzu Diversion Channel—a pride that extends throughout Niigata Prefecture. In 2024, Niigata farmers produced nearly 623,000 tons, or almost 8.5%, of the nation’s total rice production.

But as temperatures and carbon dioxide levels rise, the city and the rest of Japan are seeing an increase in white, immature grain. High temperatures damage the grain and reduce crop yields, Nitoko-Mieru Museum concierge Tomoko Saikachi said.

Diminished yields create an imbalance between supply and demand, pushing prices upward and disrupting the lives of rice farmers and those who depend upon them.

Absent a solution, Nagaoka will lose the revenue and economy that have been built by the river diversion channel and these rice paddies.

Declining salmon

Rice paddies aren’t the only food and revenue source affected by climate challenges. The diversion channel is home to many salmon habitats, but yields have been decreasing as the climate changes, Saikachi said. High temperatures are causing the Sea of Japan to grow warmer, making it harder for the fish to survive.

According to the Japan Meteorological Agency, average sea surface temperatures around Japan have risen by 1.33 degrees Celsius (roughly 2.4 degrees Fahrenheit) over the past 100 years, greater than the 0.62 degrees Celsius (or 1.1 degrees Fahrenheit) increase for global ocean temperatures. And temperatures in the portion of the Sea of Japan touching Niigata Prefecture have risen between 1.56 and 2.01 degrees Celsius—2.8 and 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit—over the century, the meteorological agency reported.

Extreme weather events also create a volatile environment for the fish. The mountains where the Shinano River originates receive less snowfall, which melts earlier. The prefecture undergoes periods of drought and heatwaves followed by intense rainfall.

Air temperatures have been steadily climbing since the 1990s, with spring months receiving abnormally warm days compared to historical temperatures. While the earlier summer months have remained consistent, August and September have received spikes in temperature, with days showing in the 100°F/38°C range and beyond. This is especially abnormal compared to reports from the 1990s that show no days at or past 100°F/38°C despite it being the height of summer.

Higher temperatures lead to another concern that will affect the people of Nagaoka and its rice farmers: an increase in heat illnesses. Due to the intensity of the new heat patterns, heat-related illnesses have been on the rise, with fatalities increasing across Japan with each passing year.

Remembering the past

Despite climate concerns and ongoing construction, the diversion channel continues to protect the Echigo Plain.

And with a century of history, the people of Nagaoka and the Niigata Prefecture try their best to honor and preserve the history and legacy of the diversion channel. For many, the weirs have always been in operation, so it’s hard to imagine a time when the channel wasn’t there to protect them. That’s why it has been so important to create spaces in which locals and visitors alike can learn more.

The Niigata prefecture is home to two museums dedicated to the channel: the Shinano River Ohkouzu Museum and the Nitoko Mieru museum. While the Shinano River Ohkouzu Museum sits right in the fork where the river and channel separate, the Nitoko Mieru museum is located farther down the channel, closer to where it lets out into the sea.

The Shinano River Ohkouzu Museum is in Ohkouzu Bunsui Park, where visitors can see the original main weir, which was registered as a national tangible cultural property in 2000, the new state-of-the-art new main weir with its hydraulic gates, fishway observatories and a variety of monuments.

Among the monuments is one built in 1931 to mark the completion of weir repair work. The inscription, by Akira Aoyama, reads: “Blessed are those who find the will of heaven in all things in the universe. For the benefit of humankind and for the benefit of the motherland.”

The park is especially popular during sakura season, when visitors flock to the area to walk among the thousands of flowering Yoshino cherry trees planted along the river.

Flood control is a global issue

Japan is not the only country to experience heavy rainfalls and an increase in flooding. In fact, protecting citizens and businesses from floods is taking up increasing attention—and funds—among governments in the Dallas-Fort Worth area.

In Nagaoka’s sister city of Fort Worth, planning and preliminary work continue for the Central City Flood Control Project, known locally as Panther Island. The central purpose of the project is to enhance flood protection for the city by diverting a portion of the Trinity River into human-made channels. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is working with state and local partners, like the Tarrant Regional Water District, to protect 2,400 acres on which nearly 3,000 homes and 750 businesses face flood risks.

The $1.16 billion project anticipates creating a human-made island—Panther Island—and offers the prospect of clearing the way for economic development near existing levees along the lines of San Antonio’s River Walk. The project has an expected completion date of 2032, although groundbreaking on the rerouting of the Trinity is not expected until early 2026.

Arlington is not immune to flooding

Arlington, Texas, has also been active in flood mitigation projects. One multi-phase project was designed to reduce the risk of flooding and enhance drainage in neighborhoods near Fielder and Randol Mill roads. The project involved stabilizing creek banks in Randol Mill Park to protect against erosion, expanding drainage culverts and enhancing storm drainage and sewer lines. The $9.5 million project was part of a larger $16.8 million initiative launched in 2019 to better manage stormwater flows.

Arlington takes flooding seriously. A draft spring 2025 Department of Public Works report, “Repetitive Loss Area Analysis,” said: “Flooding is the most common natural hazard in the United States. More than 20,000 communities experience floods and this hazard accounts for more than 70 percent of all Presidential Disaster Declarations.”

The analysis included results of a city survey of residents, which found that 22% of respondents experienced flooding on their property, with 11% experiencing flooding on the first floor. The survey also found that 17% of respondents had experienced flooding in their neighborhoods. According to the report, 28% of respondents had installed flood protection measures, including regrading of their properties and installing small drainage systems.

Flooding costs vs. flood mitigation benefits

The annual economic cost of flooding in the United States is staggering. According to a 2024 report by Democratic staff of the Joint Economic Committee, the annual cost of flooding is between $179.8 billion and $496 billion from damage to homes, businesses, infrastructure and reduced economic activity.

The report said that, while costly, flood protection expenditures more than pay for themselves, estimating that “every dollar invested in flood protection can save $5-8 in damages.”

Such figures are likely to ring true in Niigata prefecture, where the diversion channel allowed for the prefecture’s growth and development.

The Ohkouzu Diversion Channel put an end to chronic flooding along the Shinano River. In addition to allowing for the rise of productive agriculture, the channel’s work in drying out the land allowed for the construction of major transportation routes through the region, including the Joesu Shinkansen, or bullet train, and major highways. Municipalities like Niigata City were able to reclaim former river land, spurring economic development and population growth.

While a project of the scale of the Ohkouzu Diversion Channel is unlikely in the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex, the threats posed by a changing climate are sure to spur communities to turn to civil engineering projects to protect their communities just as the diversion channel has safeguarded the people in Japan’s Echigo Plain.

Lisa-Marie Akindayomi, Amaya Bean, Wilson Hasty, Chanel Le, Haylee Jenkins, Elvis Martinez-Cartagena, Isaias Martinez, Alyssa Morales, Andrew Norton, Jessyann Perez, Manhoisiam Tungnung, Xitlalic Valles and Celeste Vazquez provided additional reporting for this story.

How This Story Was Reported

This story was produced as part of a service-learning project between students at the University of Texas at Arlington, Fort Worth Sister Cities International and the Nagaoka International Exchange Association. The project was built into a summer study abroad class in Japan.

Fort Worth Sister Cities helped facilitate contact with the Nagaoka International Exchange Association and provided students with a primer on the culture and manners of Japan. Special thanks to Fort Worth Sister Cities International’s Beth Weibel, director of exchanges and outreach, and Danielle McCown, exchanges and outreach manager.

The Nagaoka International Exchange Association helped define the shape of the project and facilitated transportation, site tours and interviews. The Nagaoka International Exchange Association also provided a tour of the city government complex, the Nagaoka Fireworks Museum and shared stories about Nagaoka’s history. Special thanks to the Nagaoka International Exchange Association’s Chikako Jinnai for organizing the itinerary, arranging interviews, and keeping the team on schedule, and to Ariko Tsuchida, who shared Nagaoka history, provided real-time translations during interviews and helped with fact-checking.

Through the efforts of the Nagaoka International Exchange Association, students on July 17 visited the Shinano River Ohkouzu Museum and the Nitoko Mieru museum, where they learned from docents and exhibits, conducted interviews and gathered multimedia content. Students also conducted additional research to complete their reporting.