Texas school administrators reflect on a decade of budget changes approaching 2023’s legislative session

Wilemon STEAM Academy, an elementary school in the Waxahachie Independent School District, sits empty for Thanksgiving break on Nov. 22.

November 29, 2022

ARLINGTON, Texas–With the Texas Legislature’s 2023 session on the horizon, public schools are again anticipating a shift in budgets following 15 years of varying funding trends.

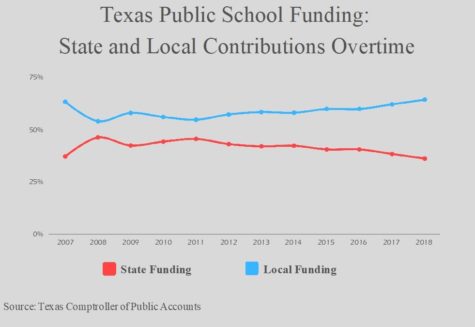

School districts receive funding through a marriage between local property taxes and the state, which determines the amount of money it will contribute to school districts in their biannual sessions.

Following the 2008 recession, the school system has seen “historic cuts” in funding from the state, said Catherine Robert, assistant professor of educational leadership and policy studies at the University of Texas at Arlington.

The cuts came primarily in the 2011 legislative session after the federal aid for the recession had ceased, Robert said. While recent sessions have ended on high notes for schools, with the state significantly increasing school funding in 2019, according to The Texas Tribune, Robert said the funds still haven’t been fully restored to what they used to be.

The state has seen an increase in what local school districts are paying for in property taxes but a continued deficit of government funding, she said. When budgeting their district, administrators have had to “fly blind” when planning their budgets for the following year.

“So when there’s a legislative session going on, [districts] have to have a series of contingency budgets in case the legislature does this or that,” Robert said. “It’s very hard to plan your year.”

Sometimes, schools must wait until May or later to hear the final funding amount. Some teachers start a school year not knowing what their paycheck will look like, she said.

The inability to agree and make collective decisions in the best interest of the school districts hurts schools’ ability to plan, sometimes leading to a mess of confused teachers and parents, Robert said.

School budgeteers need to balance effectively spending while still saving for emergencies, said Jeff Robinson, a Waxahachie, Texas, resident who worked as an elementary school principal in his city’s district from 2002 to 2014 before spending the rest of his career as the school’s technology director.

“You don’t want to keep too much of the taxpayer’s money in the bay because they’re expecting you to spend it [for] the better,” Robinson said. “You don’t want to have $50 million in your bank that’s just sitting there. There’s a pretty good, sweet spot of how much money you need to save or keep for a rainy day.”

When he worked in the Waxahachie Independent School District, about 75% of his school’s funding came from property taxes and 25% from the state, he said.

When funding is cut, schools must make tough decisions about allocating their budget, often leading to layoffs and program cutting, Robert said. Budget reductions following the great recession forced many school districts to stop their art and music programs.

There is no set rule of what school districts can or can’t do with their budgets, she said. Aside from having to follow a few course requirements, each community across the country makes its own decisions.

“A lot of library aides were cut, and in places like California, they got rid of librarians completely and shuttered libraries,” she said. “You had a whole giant library full of books that was completely shut down because they just couldn’t afford to pay for the library.”

Robinson said that when his school would budget in Waxahachie, they would look at their students’ measurable performance areas such as math scores, reading skills and attendance to determine what areas needed more funding. During talks of budget cuts in 2011, the district had to start planning to reduce staff on a “last one in, first one out” strategy. If affordability became an issue, janitors and cafeteria workers would likely be let go.

“It used to be that once you’re hired, you’d stay all year, but based on uneasiness, we didn’t know if we’d have funding,” he said. “We had to be upfront with people to say, ‘Hey, listen, you might not have a job’ because of what was happening.”

But schools in Waxahachie never had large enough budget cuts to actually call for the layoffs, Robinson said.

Since 1993, the state has tried to aid poorer school districts through a program known as “Robin Hood,” or recapture, which takes excess funding from school districts it defines as wealthy and reallocates it to poorer communities, according to the program’s website.

When the state decreased its share of funding, the program led to some school districts having worse budget cuts than others, Robinson said. Waxahachie was largely unaffected by the changes, falling in the middle of the economic spectrum.

“We were in a good gray area. We didn’t get any money and we didn’t have to give any money back so we could budget pretty accordingly,” Robinson said.

Nationwide, the first expenses that schools sacrificed in wake of budget cuts were school administrative roles, Robert said. Before cutting campus services, districts are likely to let go of central office staff like coordinators and assistant principals who work behind the scenes to run the school.

Schools either must find other sources of income to keep services running or give them up entirely. She said districts have to cut some random, unexpected services such as bus lines in wake of rising gas prices.

“It’s a community decision to talk about what they can do with the resources they have and what they want to prioritize,” she said. “Someone or something will lose out, you know, so it’s a matter of competing interests.”

Robert was working as a school administrator through the budget cuts of 2011 and said the years were a hard time to be a new teacher. Schools had to let go many of the inexperienced teachers at the time who still needed time to develop their craft.

“We had such a brutal cut, I mean it was it was distinctly less money from one year to the next,” she said.

The amount of government funding for state universities has also significantly dwindled in the last 20 years, said Karen Krause, executive director of financial aid, scholarships and veteran’s benefits processing at UTA. Rather than decreasing services and staff, funding deficits for universities lead to additional costs for students.

Increasing student cost leads more students to take out federal loans to graduate, bringing Texas’s funding issues to a national scale, Krause said. There are many different voices in deciding state budgets, and they won’t always favor education.

No matter what the year’s budget looked like, Robinson said he tried to build a system that encouraged teachers to slow down and develop relationships with children. Assuring students had clothes, food and safe living conditions was a higher priority than their grades.

“If you actually shake the kid’s hand when they walk in the door, ask them how their night was and spend a few minutes not just diving right into multiplication tables, it’s better,” he said. “Kids find out how much you actually care about them.”

Robert currently teaches future educational leaders and people going into school administrative positions. She said she always emphasizes how important it is to prioritize students and whenever making budget decisions, it’s important to hear from all parties in the community.

“It needs to be a community conversation. That includes talking to parents and school board members,” she said. “School board members need to hear from families about where their priorities lie.”